NEW! YOGA FOR OSTEOPOROSIS FUNDRAISER FOR THE ROYAL OSTEOPOROSIS SOCIETY. CLICK HERE FOR DETAILS.

For many of us, climbing is more than just a sport – it’s a way of life, and it defines who we are. And we hope we can continue climbing or enjoying the mountains throughout our lives. I know many climbers who are still very active in their 70s and into their 80s.

But as we grow older, we become increasingly at risk of osteoporosis, a very common condition which can significantly affect participation in climbing and other outdoor activities.

This article is to draw attention to the importance of bone health, and the steps you can take at any stage of life to optimise your own bone health, now and for the future.

And of course I’ll be talking about how yoga can help – whether for people living with osteoporosis, or for those wanting to develop good postural habits earlier in life.

This article is intended purely to draw attention to the prevalence of osteoporosis and its possible implications for climbing (and yoga!)

It is not a substitute for medical advice. If you have osteoporosis, or suspect you are at risk of osteoporosis, always seek advice from a qualified health professional such as your family doctor about which forms of exercise are suitable for your condition.

For more information visit the NHS pages on bone health and osteoporosis, or explore the extensive resources on the Royal Osteoporosis Society‘s website.

Why is bone health important for climbers?

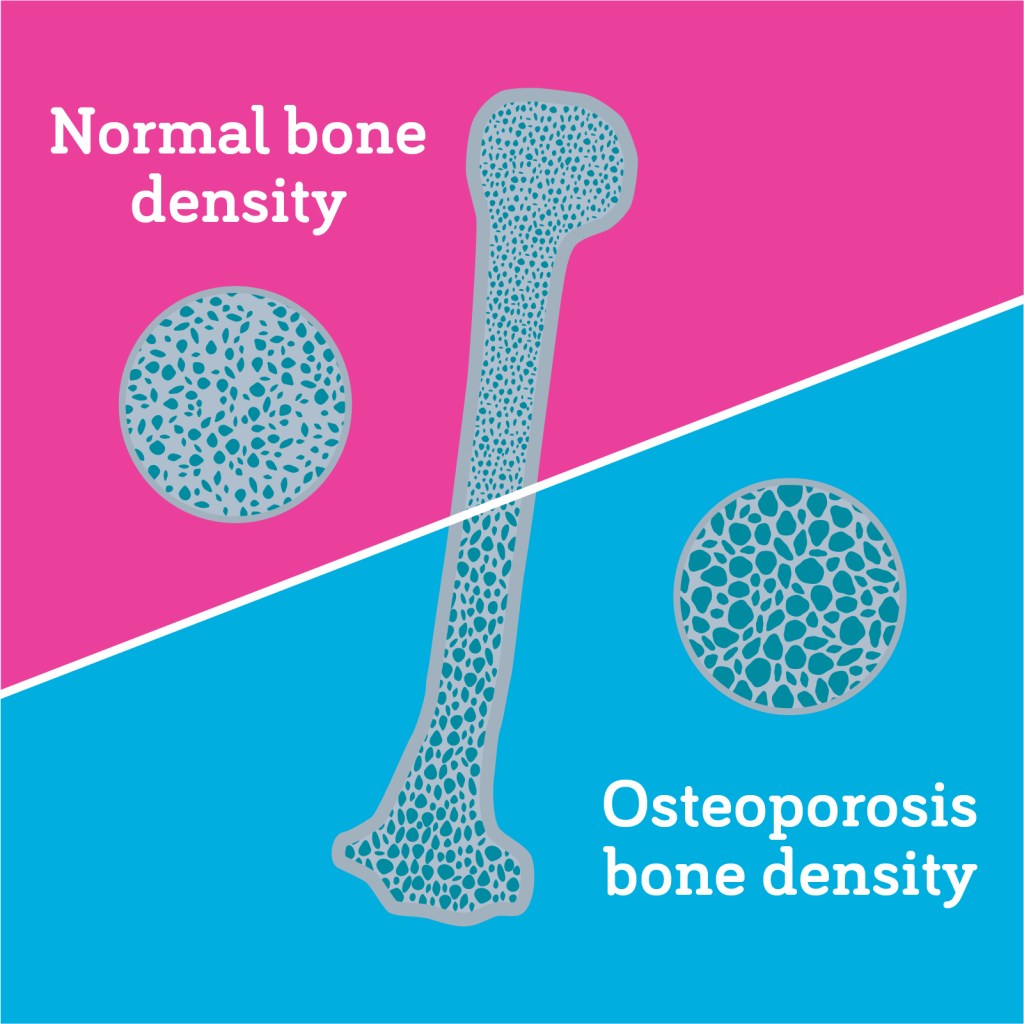

Osteoporosis is a condition in which bones lose density and strength, and become prone to fracture. It’s especially prevalent amongst older women due to hormonal changes at menopause. But it also affects men and younger people; including people who have had eating disorders, or who have needed certain medications.

In the early stages of osteoporosis, there are no outwardly noticeable symptoms, and a person may not know they have the condition until they break a bone. A bone density (DEXA) scan uses low dose X-rays to assess bone density and strength.

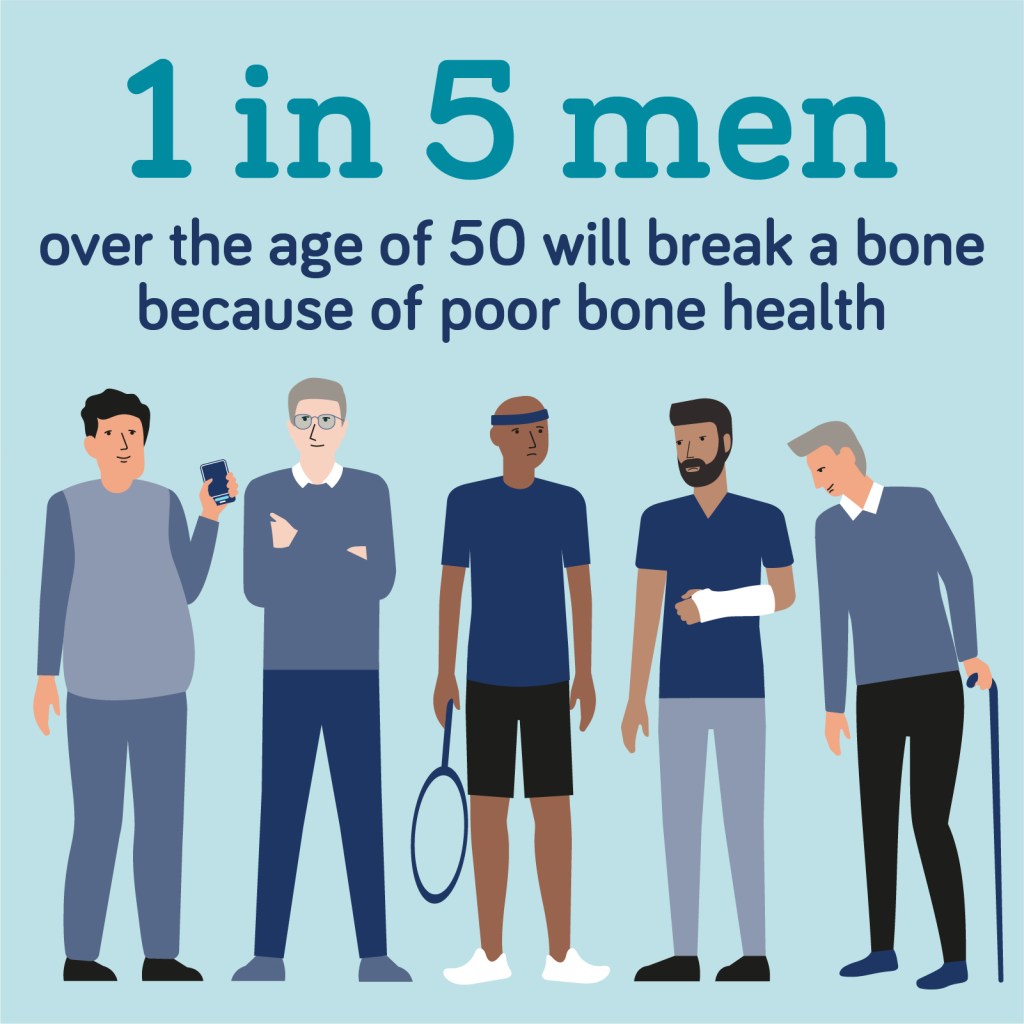

About 1 in 2 women and 1 in 5 men over 50 will suffer a fracture due to osteoporosis[i]. Because those fractures are often in the vertebrae or hips, they have a significant impact on physical activity. 1 in 2 people who experience osteoporotic fracture give up or reduce their participation in sport and exercise[ii]. And even those who make a full recovery from fracture may subsequently feel more anxious about taking lead falls, or jumping off boulders. As osteoporosis progresses, particularly following vertebral fracture, mobility in the upper back and shoulders can be impaired, making it even more difficult to continue climbing.

At the moment, the majority of older climbers are men. That’s not so surprising. When I started climbing in the late 1970s, it was rare to see another women at the crag. But participation by women has been steadily increasing over the decades[iii]. And as this rising demographic progresses to the age of menopause and beyond, increasing numbers of climbers are likely be affected by osteoporosis.

Climbing and Bone health

Although osteoporosis mainly affects older people, strong bones are built during early adulthood, and the more you can do for your bone health while you are younger, the less you are likely to be affected by osteoporosis in later life.

Although there are very few studies specifically of climbing and osteoporosis[iv], these do suggest that climbing has a positive effect on bone density. And we also know enough about general lifestyle and exercise risk factors to draw useful inferences, most of them positive, for climbers.

On the plus side, climbing outdoors is a great exercise prescription for bone health!

Bones of the legs and spine get stronger if you do plenty of weight-bearing exercise with impact – and varied impact is more benefical than repetitive impact[v][vi]. Bones also get stronger with muscle strengthening or resistance exercise, particularly important for the upper body, such as spine, arms and shoulders.

So a typical outdoor climbing day of hauling a sack of gear or a bouldering pad up a rough hillside to a crag, cranking on your arms all day, and then hauling your gear down at the end of the day is great for providing the combination of resistance and impact needed for bone health.

Furthermore, being out all day in sunshine enables your body to form Vitamin D, essential for helping your bones absorb calcium.

On the other hand, a small minority of climbers, particularly elite competitors, may find themselves at additional risk of osteoporosis later in life if they feel pressurised to reduce bodyweight to improve performance. Low bodyweight is a significant risk factor for osteoporosis, particularly if it is associated with an eating disorder or amenorrhoea (periods stopping). Studies have shown that female climbers, especially at elite levels, are at increased risk of eating disorders, with the inevitable increased risk of osteoporosis[vii].

Less serious, but much more commonly, many climbers tend to develop a ‘climber’s hunchback’ or hyperkyphosis – a rounding of the upper back and shoulders due to muscular imbalances[viii]. Not so much a problem if your bones are strong, but if you lose bone density and don’t correct your posture, it could increase your risk of vertebral collapse.[ix]

(Yoga backbends are great for strengthening and straightening the back, and reducing the risk of hyperkyphosis. A couple of gentle backbends are suggested at the end of this post, but there are many more to choose from.)

And there are also risk factors beyond your control, including your family history (there is a genetic element to osteoporosis); certain medications; and certain illnesses or health conditions (for example early menopause).

Steve’s story

Steve has been climbing for over 30 years and is now in his early 60s.

He had no idea that he was affected by osteoporosis until a minor accident last year resulted in a unusually bad fracture. A bone density scan revealed a significant loss of bone density.

Since his accident, Steve has been contending with both recovery from his fracture, and adjusting to the news that he has osteoporosis.

Not surprisingly, his diagnosis has impacted on his attitude to risk in climbing. He has stopped bouldering completely. At first he thought he wouldn’t want to lead again, but a sport-climbing holiday tempted him back into leading, though only on routes he feels are well within his comfort zone.

He is still assessing how he feels about his climbing in future. He mentions the “macho pressure” culture in climbing to keep pushing oneself despite health or injury risks. He also talks of the mental health implications of stopping climbing for someone who has always found wellbeing in the mountains.

For the present, he is still taking a cautious approach. “I’m always going to be more careful now”, he says. “It was horrendous being injured, and I want to avoid it happening again.”

Jane’s story

Jane is in her early 80s and has been enjoying outdoor activities throughout her adult life, including walking climbing, skiing, cycling and alpine mountaineering.

Right up until recent years, she and her husband had been enjoying sunny sport climbing together in France and Spain.

Although a bone density scan had shown that Jane had osteopenia (slightly reduced bone density), it did not really affect her until one day in her early 70s, when she suddenly started to experience chest pains.

Once heart problems had been ruled out, it was discovered that Jane had suffered a vertebral fracture in her upper spine.

Recovery from a vertebral fracture is slow and painful, but nonetheless Jane eventually made a good recovery and even cautiously began climbing again.

However she since experienced a further vertebral fracture in her late 70s, which has been more debilitating and painful, with discomfort increasing when walking long distances.

Reduced mobility in her upper back made climbing too difficult to continue – though Jane continues to go for a walk almost every day.

Royal Osteoporosis Society recommendations for good bone health[x]:

Maintain a healthy body weight

Lead an active lifestyle – with plenty of varied, weight-bearing, moderate- to high- impact exercise. So if at any stage of your life you need to stop climbing, try to introduce an alterative form of weight-bearing exercise.

Eat a balanced diet with plenty of calcium; if you are vegetarian or vegan consider asking a health advisor whether you need a supplement

Get enough vitamin D from the sun (or supplements if necessary, particularly if you are dark-skinned)

Avoid smoking

Regulate your alcohol intake

It’s never too early to start; strong bones built in early life will reduce your risk in later years.

Yoga for Bone Health

Yoga alone will not strengthen your bones! You need to combine it with other forms of moderate- to high-impact weight-bearing exercise such as hill-walking or running.

But yoga can complement other forms of exercise to help you protect your spine and improve your balance, and also gives weight-bearing opportunities for the upper body. Appropriately modified yoga can be very beneficial to people with osteoporosis – and if you are not yet at risk of osteoporosis, yoga can help you develop core strength, balance and good postural habits which will stand you in good stead for the future.

These poses may not be suitable for everyone. Always check with a qualified health professional before starting new forms of exercise, especially if you have, or suspect you may have, osteoporosis. If you do have osteoporosis, try to find a specialist yoga teacher, and if you have previously had vertebral fractures, careful assessment and one-to-one teaching is recommended.[xi]

See my Yoga for Osteoporosis page for details of my yoga classes for people with osteoporosis – proceeds to the Royal Osteoporosis Society.

Protecting your spine

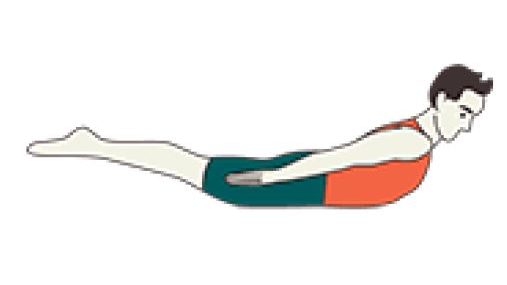

Gentle backbends such as Locust (Salabhasana) and Baby Cobra (Ardha Bhujangasana) help strengthen and extend the spine, relieving pain and discomfort and reducing hyperkyphosis (excessive rounding of the upper back).

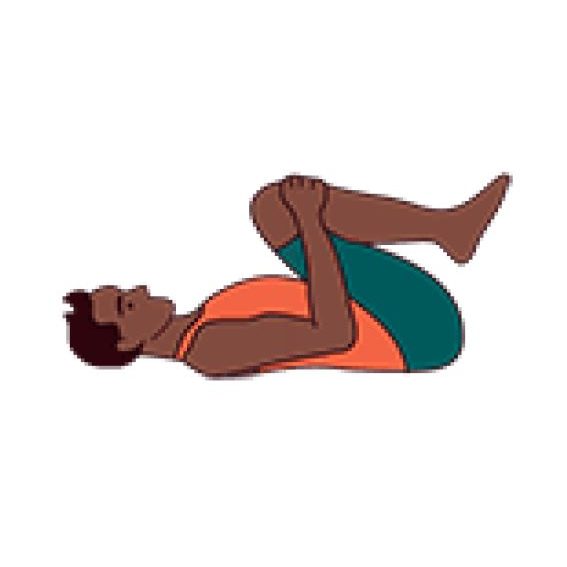

All pose illustrations copyright Tummee.com

Yoga can also be used to strengthen the core, taking strain off the spine. For example, Balancing Cat (Utthita Marjariasana) provides gentle work for the core, while for more experienced yogis, incorporating Chaturanga Dandasana in to your Vinyasa gives a more intense workout for the core as well as weight-bearing on the arms.

It’s also important to maintain hip and knee flexibility, as this enables you to avoid flexing the spine to bend down – for example to unpack a rucksack or take clothes out of a washing machine. Poses such as Garland pose (Malasana) or Knees to Chest pose (Apanasana) encourage deep flexion in the hips and knees.

Developing balance

Balance becomes very important if you have osteoporosis, for helping to prevent falls. Although poses such as Tree pose (Vrksanana) are great for challenging your balance, other more accessible standing poses such as Warrior 2 (Virabhadrasana 2) variations can also help develop your balance.

Weight bearing for upper body

Many sports and physical activities involve weight bearing on your legs, but not so many on the arms. Arm balances and poses like Downward-facing Dog (Adho Mukha Svanasana) allow opportunities to bear weight on your arms.

Poses to avoid!

If you have osteoporosis it’s important to avoid poses which involve excessive flexion (forward bending) of the spine, as there is a risk of vertebral fracture.

Examples of poses to avoid are shoulder stands (Sarvangasana), which put large loads on the upper spine, and forward folds (Uttanasana), particularly if you don’t hinge sufficiently at the hips.

For more information about exercise and bone health, see the Royal Osteoporosis Society’s exercise guidance.

Or for a detailed analyis of the risks and benefits, see this Consensus Statement in the British Journal of Sports Medicine. Not surprisingly it doesn’t actually cover climbing, but the references to skiing and horse riding at the bottom of p.841 may give you food for thought!

DISCLAIMER: ALL ACTIVITIES DESCRIBED ON THIS WEBSITE ARE FOR GENERAL INFORMATION ONLY AND MAY NOT BE SUITABLE FOR EVERYONE. ALL EXERCISE CARRIES A SMALL RISK. ANYONE TRYING ANY OF THE ACTIVITIES DESCRIBED ON THIS WEBSITE ACCEPTS THIS RISK AND THE AUTHOR DISCLAIMS ANY LIABILITY FOR ANY ADVERSE EFFECTS CONNECTED WITH THESE ACTIVITIES.

References and notes

[ii] Royal Osteoporosis Society 2022

[iii] Various studies show participation by women increasing from around 15% in the 1990s to around 30% today. Today, nearly 50% of climbers under 18 are female, compared to only 20% of climbers over 65.

(BMC 2003, Ankers and Kay 2021. Thanks also to UKClimbing for sharing survey results regarding climbers’ gender and age.)

[iv] A literature search uncovered just two studies directly related to climbing and osteoporosis. In both studies, the participants were young males, the demographic at least risk! Kemmler et al 2006 concluded that climbing promoted bone mineral density (BMD) in all body regions except the skull, whereas Sherk et al 2010 concluded that climbing promotes BMD in the arms and legs.

[v] Frost, H.M, (1987) Bone mass and the “mechanostat”: a proposal

[vi] Kang YS, Kim CH, Kim JS (2017) The effects of downhill and uphill exercise training on osteogenesis-related factors in ovariectomy-induced bone loss

[vii] For example Joubert, Gonzalez and Larson (2020) Prevalence of Disordered Eating Among International Sport Lead Rock Climbers

[viii] Gymclimber.com Let’s End the Climber’s Hunch Epidemic; Mojagear.com Four Simple Ways to Combat Climber Posture

[ix] Huang et al (2006) Hyperkyphotic Posture and Risk of Future Osteoporotic Fractures; Sinaki et al (2002) Stronger back muscles reduce the incidence of vertebral fractures

[x] Royal Osteoporosis Society Bone Health Checklist

[xi] Brooke-Wavell et al (2022) Strong, steady and straight: UK consensus statement on physical activity and exercise for osteoporosis