You know that yoga is supposed to improve flexibility, but what’s the best way to gain the improvements you want to see? This article is particularly aimed at climbers who are new to yoga, or who are struggling with flexibility. However, even experienced yogis can benefit from learning more about the physiology of stretching. And once you’ve understood some fundamental principles of stretching through yoga practice, you can apply them to specific poses shown other articles on this website.

⚠The suggestions given here are not a substitute for medical advice.

If you have a problem with inflexibility or pain in any of your joints, always seek advice from a qualified health professional such as your family doctor or a physiotherapist about which forms of exercise are suitable for your condition.

What do we mean by ‘flexibility’?

This might sound obvious at first, but it’s worth considering more precisely what this word involves! Flexibility is the ability of joints, muscles and soft tissues to move through an unrestricted and pain-free range of motion.

Flexibility is joint-specific – some joints aren’t intended to move at all, while joints like the hip potentially have a very wide range of motion. It’s also movement-specific – a joint may move more freely in some directions than others.

Many factors can affect joint mobility, including tightness in muscles and associated connective tissue, body shape and composition, gender, injury, and health conditions1.

The information in this page focuses on tightness in the muscles and their associated connective tissues (referred to as muscle units), a factor which can be improved by stretching and regular yoga practice.

However, if you have any of the conditions below, it’s best to seek personalised advice about whether it’s safe to stretch, and whether there are any movements you should avoid (select condition for more information).

If you have an injury which affects your flexibility…

If you are recovering from an injury which is affecting any of your joints, it’s important to get clearance from a physiotherapist before starting or returning to yoga. In many cases, a carefully planned yoga routine may aid the final stages of your recovery and reduce the risk of injury in future, but it’s important to get personalised advice to check that you’re ready for this stage.

If you have a health condition such as osteoarthritis…

Arthritis is a very common condition in which the smooth cartilage of a joint becomes so damaged and worn down that the joint no longer articulates (moves) easily and becomes inflamed and painful. While arthritis cannot be reversed, it can be managed, and some mobility restored, through careful and appropriate exercise. If you have any sort of health condition which is affecting your flexibility, get advice from your doctor or physio first, and if possible look for a yoga teacher specialising in supporting students with health conditions.

If you’re hypermobile…

Hypermobility is the ability to move joints further than the majority of people. It’s possible to be hypermobile in some joints but not in others. If you are hypermobile, it’s best to avoid stretching to your full range of motion, and instead see your yoga practice as a way to develop stability, strength, alignment and body awareness.

If you’ve had a hip replacement…

Following a hip replacement, mobilising and stretching exercises will be an important part of your rehab, but must be done with the guidance of a physiotherapist at first. When you are cleared to return to a wider range of activities, ask for advice about the movements that are appropriate for you. General guidance following hip replacement states that the hip should not be flexed beyond 90°, and that outward rotation of the hip (e.g. sitting cross-legged) should be avoided.

How does stretching improve flexibility?

Tightness in muscles is generally due to them being maintained in a shortened position for too long. This shortening may sometimes be due to the muscle contracting in use, but more often is due to muscles being passively shortened for prolonged periods. For example sitting at a desk all day with hips and knees flexed will result in tight hamstrings and hip flexors.

It’s intuitive to think that stretching works by ‘making your muscles longer’. However, the actual mechanism is more nuanced (and a continuing subject of debate in sports science!) Multiple studies show that stretching does not actually lengthen muscles in the long-term. Instead it increases the ability of the muscle to move in and out of a fully elongated position.

Muscle units contain sensors (proprioceptors) which detect the elongation of the muscle and the tension in the associated tendon. These normally protect tissues by inhibiting too much elongation. However, if the muscles spend too long in a shortened position, this effect becomes overprotective, and the muscle can no longer elongate normally.

Current theories suggest that if stretches are held for long enough, this trains the nervous system to tolerate gradually increasing lengths before before further elongation is inhibited23. So stretching doesn’t result in permanently elongated weak muscles, but in more elastic muscles, effective through a greater range.

This type of stretching, in which the muscle is stretched to a point of mild tension and then held, is called static stretching. If the stretch is gradually deepened as you hold it, this is called developmental static stretching.

Widely accepted guidance is that stretches should be held for 30-60 seconds for this effect to take place4. If you are an older climber, a 60 second stretch may be more effective. There is very little evidence that holding stretches for longer than 60 seconds increases the effectiveness of the stretch.

Are there different types of stretching?

| Dynamic stretch | Joints are gently and repeatedly moved within their normal range of motion to lubricate and warm the joint. This is usually done at the start of a yoga session during the mobilisation phase. Example: Cat-cow flow. |

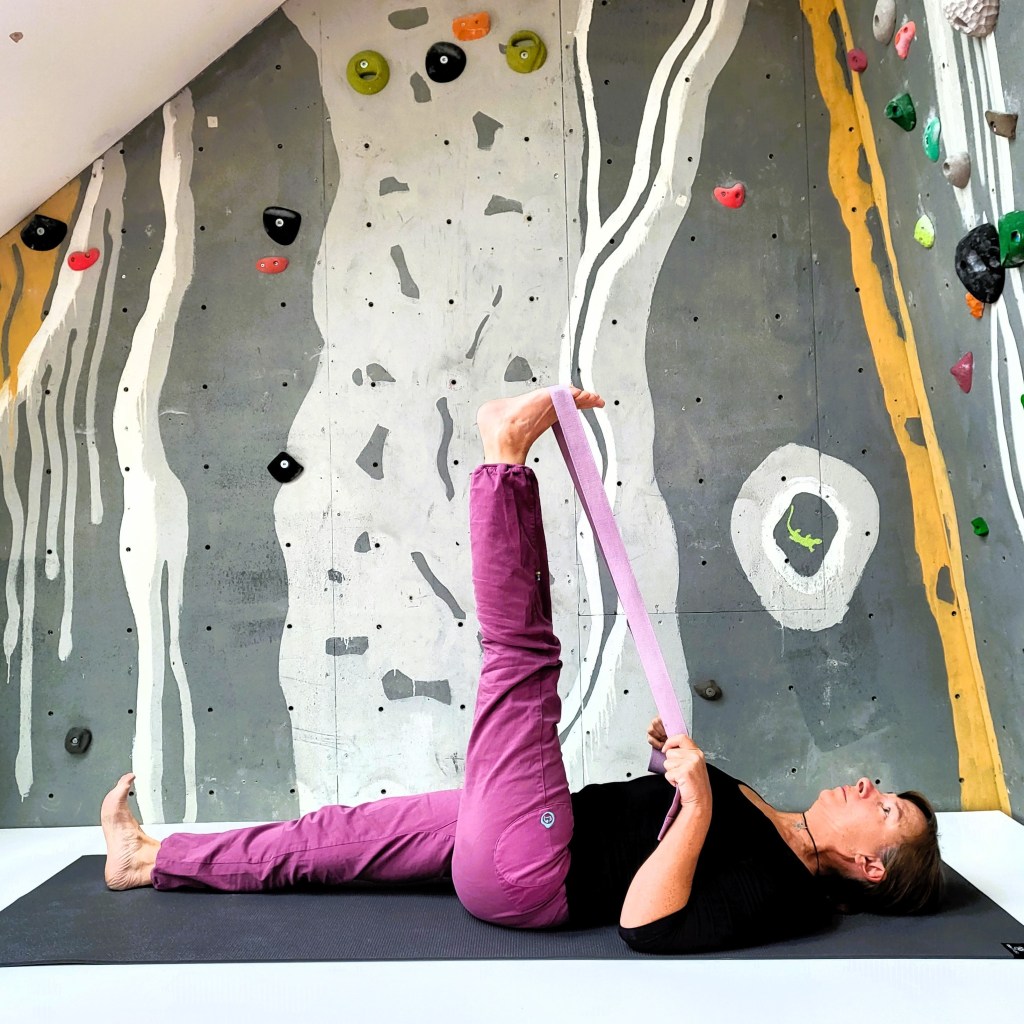

| Static stretch | As stated above, this is the type of stretching most commonly used to increase flexibility. The muscle is stretched to a point of mild tension, and then held about 30-60 seconds. A developmental stretch is a version of static stretching in which the stretch is gradually deepened as it is held. This is generally done towards the end of a practice when the muscles and joints are fully warmed. Example: Reclining hamstring stretch. |

| PNF stretch | (Not typically part of a yoga practice). A type of stretching which overcomes the neural reflexes to allow the muscle to relax further into the stretch. Best done with a trainer at first, though once you understand the principles you can try it yourself. |

| Ballistic stretch | ⚠ (Included here only to warn you against it!) The momentum of the body is used to deepen the stretch, for example bouncing the trunk downwards to touch the toes. This style of stretching, once quite popular, is now considered to have a very high risk of injury. |

Antagonist muscles and stretching

For many muscle actions, there is an opposing (antagonist) muscle that performs the reverse action. So for example, the hip flexor muscles work to flex (bend) the hip, while the gluteus muscles serve to extend (straighten) the hip.

Due to a reflex action, you can help to release a tight muscle by contracting the antagonist muscle. So, for example, squeezing the gluteus muscles in Camel pose will help release the hip flexor muscles.

Gaining flexibility through yoga

To many of us, increasing flexibility through regular yoga practice feels much more holistic, enjoyable and rewarding than tacking on stretches as a ‘chore’ at the end of a workout or climbing wall session.

Which style of yoga is best for stretching?

| Hatha yoga | This is the most commonly-encountered style of yoga, in which a short mobilisation and warm-up is followed by poses which are held (or deepended) over several slow steady breaths. This style of yoga is well-suited to making gains in flexibility and is accessible to beginners of any age. |

| Vinyasa, Power, Flow and Ashtanga yoga | These are all characterised by a rapid flow of poses linked by dynamic sequences called vinyasas. These types of yoga are great for building strength and endurance, and will help maintain any flexibility you already have, but poses are not held for long enough for the muscles to release fully. They are also less suitable for beginners. |

| Yin yoga | Poses are held for much longer, typically about 5 minutes each. This style of yoga can be very relaxing, especially if you need a rest day, but it may feel a little slow-paced for climbers. (Note also that most sports science research suggests that a 5 minute stretch is no more effective than a 60s stretch for improving flexibility.) |

| Iyengar yoga | Not so much a style of yoga as a rigorous style of teaching yoga. At a class led by an Iyengar-trained teacher5, you are likely to hold poses long enough for the muscles to relax, though you may cover fewer poses as classes tend to be slower-paced. |

Incorporating stretching into your yoga practice

Stretching can either be incorporated into a your all-round yoga practice, or you could dedicate a session to stretching (lovely for a rest day).

Your warm-up should include both a pulse raiser (for example aerobic exercise or sun-salutions) and mobilisation (gentle dynamic movements and stretches through all the major joints), before you begin any developmental stretching. A couple of possible practice structures are shown below, though of course there are plenty of other combinations:

| All-round yoga session |

|---|

| Mobilisation Sun salutations All-round vinyasa flow Stretching poses Savasana |

| Rest-day yoga session |

|---|

| Gentle walk, run or cycle before you start your yoga practice Mobilisation Stretching poses Savasana |

Using your breathing for guidance

Yoga’s focus on breathing is great for timing your stretch. Holding a pose for 5 to 6 slow steady breaths will give you approximately the 30 second stretch you need. You can also use your breathing to guide you deeper into your stretch, lengthening on the inhale and sinking deeper into the pose on the exhale.

Flexibility ‘Dos’ and ‘Don’ts’

| ✅ Do | ❌ Don’t |

|---|---|

| Warm-up with gentle aerobic exercise and mobilise your joints before moving into deeper stretches. Use your breathing to time your stretch. 5 or 6 slow steady breaths usually take around 30 seconds. You can also use breathing to guide you in deepening your stretch. Where appropriate, engage antagonistic muscles to help release the muscle you want to stretch. Stretch each muscle group several times in a session – but you can mix it up by choosing different poses each time. For example, Forward Fold (Uttanasana), Downward Dog (Adho Mukha Svanasana) and Reclining Hamstring Stretch (Supta Padangushthasana) all stretch the hamstrings. Stretch frequently – at least 2-3 times a week, or every day for fastest gains | Don’t do long (more than 60s) stretches immediately before climbing session, as this can temporarily reduce muscle strength6. For a yoga warm-up, try a gentle flow sequence or some sun salutations. Don’t be tempted to stretch too far. Aim for the point of ‘sweet discomfort’, where you feel gentle tension, not pain. If the pull of gravity is deepening a pose too far, use props to support you at that sweet spot. Don’t give up! It’s taken months or years for your muscles to get this tight, so don’t expect dramatic results within just a few sessions. Flexibility progresses millimetre by millimetre, but if you persist, you’ll get there. |

Millimetre Miracles

Well-known Canadian yoga teacher and teacher-trainer Fiji McAlpine refers to these small progressions in flexibility as ‘millimetre miracles’. If you love yoga and see it as a lifetime journey, those millimetres will soon add up.

“Millimeter miracles are the path of personal evolution, never underestimate the power of small steps along the right path.”

DISCLAIMER: ALL ACTIVITIES DESCRIBED ON THIS WEBSITE ARE FOR GENERAL INFORMATION ONLY AND MAY NOT BE SUITABLE FOR EVERYONE. ALL EXERCISE CARRIES A SMALL RISK. ANYONE TRYING ANY OF THE ACTIVITIES DESCRIBED ON THIS WEBSITE ACCEPTS THIS RISK AND THE AUTHOR DISCLAIMS ANY LIABILITY FOR ANY ADVERSE EFFECTS CONNECTED WITH THESE ACTIVITIES.

References and notes

- Appleton, B (1996) Stretching and Flexibility: Everything you never wanted to know Massachussetts Institute of Technology ↩︎

- I’m deliberately using the rather generic term nervous system here, because there are different opinions about exactly how this happens. For example Bandy et al (1998) suggest that this happens at a local level, training the proprioceptors in the muscle to inhibit the stretch reflex, whereas Wheppler and Magusson (2010) argue that the brain itself learns to tolerate signals of discomfort from the stretched muscle. ↩︎

- Magnusson, P and Renström, P (2006) The European College of Sports Sciences position statement: The role of stretching exercises in sports, European Journal of Sport Science, 6:2, 87 – 91 ↩︎

- ACSM (2021) ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription, 11th Edition, American College of Sports Medicine ↩︎

- Iyengar refers to the style of teaching, not the style of practice. Iyengar Teachers undergo a rigorous training programme to give very precise instruction. There is a trend now of less rigorously-trained teachers to label their classes as “Iyengar Yoga”, but if a teacher does not have an Iyengar Certification Mark, they cannot claim to be teaching Iyengar Yoga. (And no, I’m not Iyengar-qualified myself, but some of my favourite yoga teachers are!) If you’d like to try it, find your nearest Iyengar-trained teacher at https://iyengaryoga.org.uk/search-iyuk/ ↩︎

- A static or developmental stretch lasting for over 60 seconds can temporarily reduce the ability of the stretched to pull effectively. This why long stretches should not be done immediately before a climbing session. This temporary effect has been shown to last less than an hour. In the long-term, muscle effectiveness is enhanced by allowing them to contract over a greater range. See for example Kay, A. D., & Blazevich, A. J. (2012). Effect of acute static stretch on maximal muscle performance: a systematic review. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 44(1), 154-164. [Institutional repository pre-print version]. ↩︎