CLIMBING through middle-age and beyond

(with a little help from yoga)

The gradual loss of physical performance with age can be frustrating for any keen climber, and at times disheartening. We sometimes lose sight of how fit and active we are compared to other people our age, and how climbing keeps us healthy and motivated. In this article I attempt to find the balance between an acceptance of the inevitability of aging, and a determination to keeping enjoying both climbing itself, and its physiological benefits.

It’s very much a personal take, but draws on my qualifications and experience in teaching yoga for older adults, and on published sports science research.

A little more than 20 years ago, I celebrated my 40th birthday in Sardinia. The day after my birthday, crimping on a thin limestone slab, I tore tendon pulleys on two adjacent fingers of my right hand.

Although I’d been climbing since my teens, it was my first significant injury, taking several months to recover full strength. “This is it,” I thought. “I’m old now. It’s downhill from here.”

The crimpy slabs of La Poltrona, Sardinia, where I injured two finger pulleys the day after I turned 40. (If you recognise the draw picked out by the arrow as a Mamba, this article written with you in mind 🤣.)

Yet now in my 60s, I’m still climbing routes nearly as hard as I did in my younger decades. Meanwhile my older friends in their 70s and even 80s crank up the overhangs at my local wall.

The first section of this article explores why older climbers are usually fitter and more active than our non-climbing contemporaries, and why we feel motivated to continue. After that, some reflections on how we can continue to enjoy climbing as we grow older. And finally, some yoga tips to help keep us climbing.

PART 1: HOW CLIMBING KEEPS US YOUNG

Two Yoga Worlds

This article was originally inspired by the contrasts between my two yoga worlds: yoga for climbers (including myself); and my volunteer work for health charities.

I’ve been climbing all my life, and belong to a club in which many members older than me still climb regularly. My mother still occasionally climbed in her late-70s, my father into his mid- 80s. My expectations of what older adults can achieve physically were based on these experiences.

Then a few years ago, I qualified as a specialist yoga teacher and started volunteering for health charities, teaching yoga to adults over 50. I quickly had to reassess. The difference between my clients and the climbers I knew went far beyond their minor health issues. Matwork never got off the ground – literally. Many clients told me that if they got down on the floor, they’d never get back up again. Even standing poses were a challenge for some and now my classes are mostly chair-based. I undertook further training and qualifications in working with typical older adults and now really enjoy the challenge and rewards of teaching accessible but meaningful yoga.

A Hierarchy of Functional Ageing

But it opened my eyes to how different climbers are from the average population, and prompted me to look into it further. As active climbers, do we really appreciate how lucky we are to have these levels of fitness, and climbing as a continuing source of motivation? Only around half of the UK’s 55+ age group meets the minimum recommended physical activity levels of 150 minutes of moderate exercise per week, and the proportion gets smaller in older populations1.

Sports gerontologist Waneen Spirduso (1995)2 developed a model of functional ageing to categorise the huge variations in physical fitness of older adults, which don’t necessarily correlate with actual age in years.

It’s helpful to look at where most active climbers sit on this hierarchy. Any climber who gets out a couple of days a week comes in the top two categories – so many of us can already congratulate ourselves on being in approximately the fittest 10% of the older adult population3.

And we can all think of many older climbers who would fit into the Elite category – those climbing the hardest grades, big walls or extreme alpine routes, or competing in the vet categories of major competitions.

Physical Activity and Ageing

Everyone will eventually experience normal ageing, the natural and gradual deterioration of physiological function with age that is not caused by disease4.

However, the rate it occurs, and the effect it has on us, depend hugely on the amount of physical activity we undertake regularly, with regular moderate exercise helping to maintain the health and function of many body systems.

I’ve noticed that many climbers are at first reluctant to accept the inevitability of ageing, instead blaming themselves for being out of condition, for not training hard enough.

It’s worth trying to find that balance between acceptance that some deterioration in performance cannot be prevented no matter how hard we train, while recognising that continuing to be as active as possible will help to slow down and mitigate the ageing process.

The boxes below summarise what to expect as part of normal ageing – but also the benefits we can gain from continuing to climb and exercise fully. As you read them, reflect on the full workout we get during just a typical day climbing outside. The aerobic and cardiovascular work on the walk up to the crag (usually with a heavy sack or pad), the full-body strength and flexibility work while actually climbing, the bone strengthening benefits of impact and resistance exercise. And all this for considerably more than the 150 minutes per week guidelines.

“If your goal is to keep yourself from sagging, I can’t imagine a healthier game than climbing.”

John Hoffman, Bishop CA (climbing 7b/c in his 70s) 5

What Keeps Climbers Active for Longer?

Why are many older climbers still active enough to remain in the physically fit categories while their non-climbing contemporaries are becoming more sedentary? What’s the source of our continuing motivation?

A simple answer might be that we climb because we enjoy it. And of course we do. We enjoy the movement, the challenge, and that unbeatable buzz when we succeed – on a move, on a route, or on a summit. Plus we enjoy being outside among nature, and being in the company of friends. In other words, we are intrinsically motivated.

But for many (most?) of us, there’s more to it than that. Climbing outdoors is an example of a serious leisure activity – an activity which requires a considerable investment of time, equipment and skill acquisition. Serious leisure activities are characterised by the need to attain competences, and by a strong sense of identity as a member of a social world (Stebbins 1982)6. We travel widely to new mountain areas or crags, spending most of our free time in pursuit of our passion. And in climbing, commitment is also intensified by the risk of injury or death if we get it badly wrong.

This level of commitment leads us climb even when we don’t feel like it, when we’re not going well, when the weather or our surroundings are uninspiring. We train: on indoor walls, on fingerboards, or with weights to maintain strength; walking, running or cycling to maintain our aerobic fitness; yoga or stretches to maintain flexibility.

So sometimes our motivation becomes extrinsic, or goal-oriented. But though the motivation is extrinsic, it is self-imposed (also known as autonomous extrinsic motivation7,8). To perform well on that big route. To prepare for that special climbing trip. And more subtly, but very importantly, to maintain our own identity as a competent climber and member of the climbing community.

A uniquely British form of extrinsic motivation?

By contrast, an older person attending fitness classes or a conditioning gym because of health guidelines or on medical advice has motivation externally-imposed (aka controlled extrinsic motivation). And these motivations are generally pretty negative – to avoid the bad stuff, such as heart attack, stroke, diabetes, frailty or loss of independence.

(My training in teaching yoga to older people had a whole module on motivating older clients to exercise. “So you can still walk down to the shops!” we were expected to say. “So you can still lift a kettle!”)

Excuses, excuses

The problem with externally-imposed motivation, such as medical advice, people are much less likely to continue or persist than if they are intrinsically motivated. If they don’t actually enjoy an activity, it becomes tempting to make excuses, to “allow” themselves to not to exercise, for example because of a minor injury, work pressure, family commitments etc.

(I’m sure we all know of climbers who have been medically-advised not to climb while they recover from injury or illness – but have insisted on climbing regardless, simply because they can’t not climb…)

Celebrating an 80th Birthday

On a recent climbing tour of Montenegro, I was lucky enough to meet the amazing Gaby, a climber from Munich. She was celebrating her 80th birthday with a climbing trip to the Stari Bar area with her son.

Gaby caught what she refers to as the climbing “bug” over 60 years ago. “If you catch it, you have a wonderful life full of passion,” she says. She has a bucket list ambition to lead a route on her 100th birthday.

According to Gaby, “Intrinsic motivation is extremely important for older climbers to keep on going. Climbing makes me so happy, feeling alive and strong and content”.

PART 2: MAKING THE MOST OF BEING AN OLDER CLIMBER

In recent years it’s become increasingly common that I find myself the oldest climber at the crag (or certainly the oldest female climber). While it may be easy to see this as a negative, it needn’t take much of a mindset shift to instead see this as an achievement and a triumph. I’m still out here, and I’m still climbing.

Here are some of the things I’m learning to enjoy about being an older climber. Of course it’s a very personal view, but I hope some of it will resonate with other climbers.

More Free Time

For many of us, our 30s, 40s and much of our 50s can feel like a relentless treadmill of juggling work and childcare commitments, while climbing is squeezed into the gaps between. For those of us lucky enough to find these commitments eventually easing in our 50s or 60s, we start to have a little more time for our own interests.

For me, more leisure time doesn’t just mean more time spent climbing or training. It also means more positive rest days, more time for yoga and stretching, and for complementary forms of exercise like walking or paddleboarding. And it means less pressure to pack the climbing in, if conditions are poor or if I’m just not feeling like climbing that day.

So with more leisure time, fitness can be maintained, and even developed – not only through increased load, but through appropriate rest and recovery as well.

Experience and Judgment

A friend of mine often says, “There are old climbers, and there are bold climbers, but there are no old, bold climbers”.

While this might not be quite true, most of us still climbing later in life will have picked up experience and judgement to help make the right decisions and stay calm in difficult situations.

From managing ropework on a multipitch route, to juggling tides and waves on British seacliffs, to dressing appropriately for winter mountain weather, it’s great to have the experience to keep calm when younger, less experienced climbers might be at a loss.

So even if I’m not cranking as hard as I used to be (and to be honest, that was never very hard!) I still love the challenge of getting myself into amazing places. And that feeling of being competent and in control is a reward and motivator in itself.

Finding Efficient Ways to Move the Body

Sometimes it has seemed to me that every new injury leads to a new climbing technique to compensate. Pulling on straight arms to avoid exacerbating elbow tendonitis; climbing open-handed (and taped up!) to avoid pulley tears; placing feet in line with my body’s centre of gravity to reduce knee strain. And after the injury has healed, there’s one more tool in the box to help climb with less drain on energy and less strain on tissues.

Meanwhile, I’ve always relied on bridging and palming against the rock to take the weight off my arms until it’s really needed. Using the skills gained over a lifetime to get up the rock when less experienced climbers have to rely on strong muscles!

Meeting and Encouraging Younger Climbers

Most of us remember older climbers who made a big impression on us when we were young. Now it’s our turn to be that inspiration. To enjoy sharing beta about destinations, routes, gear. To admire, encourage and praise (it beats grumbling and muttering about “wall-bred” climbers). And to enjoy vicariously that unadulterated enthusiasm that can be hard to recapture later in life.

When I was younger, there were only a handful of older women climbers as role models. It’s great to see that trend turning, and I hope young women climbers today have plenty of role models to choose from.

( …But having said all that, it does feel great occasionally to burn off someone decades younger. Last year in Sicily I retrieved the quickdraws from a route that a couple of young locals had failed to complete. I was happy to help, but it was also hard not to feel smug.)

Some Personal DOs and DON’Ts

There are hundreds of websites out there offering advice on nutrition and training for older athletes. I’m not going to attempt to reproduce or select from that wealth of advice.

But here are four pointers I try and remind myself to stick to:

DO take adequate rest. Our body systems need longer to recover from exertion than they once did. Luckily this comes at a stage of life when many of us have more free time. Maybe we climb fewer routes in a day; or take rest days more often than we used to. (I sometimes need two rest days in a row to recover completely). But conversely…

DO keep training if you are not climbing for any length of time. We lose muscle strength and fitness much more quickly than when we were younger, and just a few weeks break from climbing can leave us feeling surprisingly weak and unfit.

DON’T compare yourself to top older climbers. We wouldn’t expect a random 32-year-old to climb like Adam Ondra, so we shouldn’t beat ourselves up if we can’t do The Bells! The Bells! at age 74. Older climbers are on an ability spectrum just like climbers of any age.

DON’T compare yourself to your younger self unless it’s to your much younger self. It might be fun to revisit routes we once did as beginners, and wonder what the fuss was about. But if we try revisit the routes we did at our physical peak, it’ll likely end in tears.

PART 3: YOGA TO KEEP us CLIMBING

Feel free to ignore the rest of the article if you’re totally uninterested in yoga. But if you are starting to notice the effects of age on your climbing performance, now is a great time to start yoga, even if you have never tried it before.

Not only does yoga help us maintain climbing performance by developing flexibility, tone and balance, but its focus on mindfulness and body-awareness enables us to do so without placing undue demands on our bodies. Whatever level we practice at, we can benefit from being in tune with our bodies, from mindfulness, and from awareness of the breath.

Plus, like climbing, yoga is an activity which many people feel intrinsically-motivated to practice, for enjoyment and well-being in the moment.

Below are some poses which will complement your climbing, focusing on maintaining flexibility, pre-climb mobilisation, and re-setting the body imbalances that can result from climbing.

(Alternatively, if you already a keen yogi and have a class or routine you want to stick to, skip to the Safety Points section below for suggestions on how to adapt your practice to keep it safe and beneficial.)

⚠ If you are feeling the effects of ageing or if you have a chronic health condition, and you have not tried yoga before, you should seek medical advice before starting a new form of exercise.

If any of the following poses or movements cause pain, discomfort, or ‘just don’t feel right’, stop and move out of the pose immediately. Consider trying an easier variation, or if needed, seek face-to-face advice on how to make the pose accessible.

Yoga for Mobilisation

Getting the body gently moving is important for any warm-up, and especially if you are an older climber. These movements loosen the muscles and allow joints to become lubricated, helping you to move easily and freely. These are the movements I start almost every practice with – whether I’m teaching a class or just doing yoga for myself.

Hip Circles Pavanmuktasana variation

Bring knees towards chest and circle in opposite directions. Breathe steadily as you explore the range of motion in each hip. 8-10 circles each way.

Windscreen Wiper Twist Supta Parivrtta variation

With knees raised and feet mat-width apart, allow the knees to flop from side-to-side like a pair of windscreen wipers. Movements can be very small, or quite large with knees coming close to the mat to add in a gentle quad stretch.

Cat Cow Bitilasana Marjaryasana

Set yourself up in tabletop (all-fours), knees under hips, hands under shoulders (or slightly further forward if thats more comfortable for you).

Exhale to tuck the tailbone, round the lower back upwards, and allow the gaze to come to your knees. Inhale to let the belly drop, tilt the chest forwards and take the gaze straight ahead of you.

The following three poses can be done as a sequence. Use a folded blanket or towel under the knees if this makes it more comfortable. From tabletop take left leg out to the side, then push your upper body upright. After you have done all three poses, switch legs and do them on the other side.

Slide left hand down the left leg, then reach the right arm over.

Return to centre, then take the right hand down to the other side. Sweep the left arm over.

Half Circle Pose variation Ardha Mandalasana variation

From centre, place right hand directly in front of right knee. Turn your chest to the left and stretch the left arm up.

Restoring your Muscle Balance

Climbing tends to tighten certain muscles (typically those in the front of the body, for example the pectoral muscles, hip flexors and quadiceps), while other muscles may become lax (typically those in the back of the body such as the glutes and spinal extensors).

Your yoga practice is a great opportunity to restore that balance.

| Good for beginners! 😊 |

Stretches quadriceps and hip flexors. Tuck your tail under and engage your glutes for maximum benefit. Blocks help you sink fully into this pose without to much pressure on the knees.

Add a chest opener…

Stretches quads, hip flexors and chest. Engages glutes and core.

| For more experienced yogis ⚠ |

Camel Pose Ustrasana

Opens quads, hip flexors, shoulders and chest. Keeping the toes tucked makes the backbend more accessible and also gives a lovely stretch if your feet have been squeezed into rock shoes for days.

This pose is NOT SUITABLE FOR BEGINNERS – see below for an easier variation.

Try Baby Camel instead…

As a climber, you probably already do forearm stretches, but they work nicely as part of a yoga routine and feel less of a chore if you do them as part of your practice. I like to include both passive and active stretches to reduce the risk of injury in both fingers and elbows.

An active forearm stretch engages the antagonistic (extensor) muscles to help release the wrist and finger flexors. Stretch the arms out at shoulder height with the palms facing outwards. Feel as though you are trying to bend the fingers back towards the ears.

Safety Point 1: Protecting the Spine

Many yoga classes and routines involve forward folds. If you are tight in the hamstrings or hips, it can be tempting to deepen the fold by overflexing the trunk, rather than hingeing at the hips. This risks injury to vertebrae, discs, and surrounding muscles.

Instead, try bending the knees to release the hamstrings, and fold forward only as far as you can do so while keeping the back straight.

Better to allow the knees to bend and release the hamstrings enabling the hips to hinge and the spine to remain straight.

Yoga poses which increase your hip and knee flexibility will help keep your back safe, because you can squat and bend down without straining your back (especially important when lifting).

| Good for beginners! 😊 |

Half Knee-to-Chest Pose Ardha Pawanmuktasana

A good way to start exporing and developing your hip flexibility. Gently pull knee towards chest, just as close as causes no discomfort. Take a few deep even breaths, then repeat on other side.

| For more experienced yogis ⚠ |

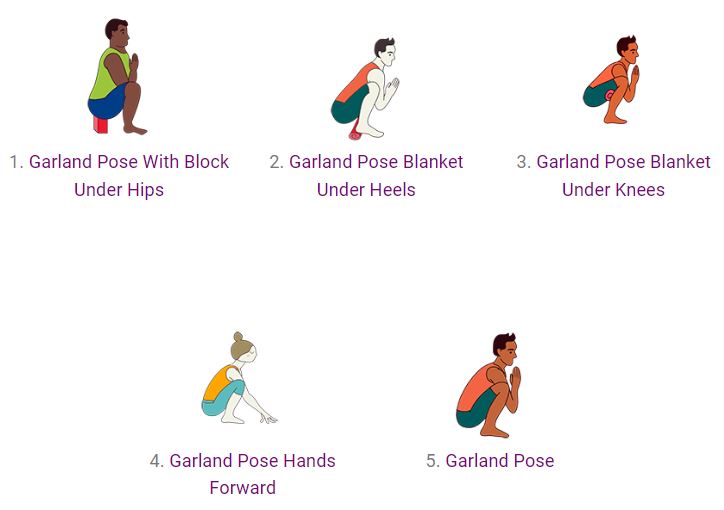

Garland Pose Malasana

involves deep flexion in the hips and knees as well well as opening the groin. This can make it challenging, but there are lots of easier variations

Easier variations of Garland pose…

Hand-to-Toe Pose with strap Supta Padangushthasana variation

The safest way to stretch your hamstrings for hip flexibility, as your back is supported throughout. Your leg does not have to be straight – just aim for a gentle stretch behind the knee.

For more poses like this see my article on Yoga for Flexible Hips (though keep in mind that some of the poses may not be suitable for older climbers)

Downward Dog Pose Adho Mukha Svanasana stretches hamstrings and calves as well as developing shoulder stability – but only if done with good alignment. Allow your knees to bend and your heels to rise in order to get your back long and straight first – then lower heels gently for the stretch along the back of the leg.

Safety Point 2: Care with Hip Rotation

Outward rotation of the hip (such as when sitting cross-legged) is very useful to maintain for climbing so long as your hip joint and the neck of your femur are healthy.

However, if you have arthritis of the hip, low bone density in the hip, or especially if you have a replacement hip, outward rotation of the hip should be avoided unless you have been cleared to do so, for example by an orthopedic surgeon, rheumatologist or physiotherapist.

Poses to avoid (unless advised otherwise) if you have any of above hip problems include:

- Cross-legged (Easy) Pose Sukhasana

- Cobblers (Bound Angle) Pose Baddha Konasana

- Pigeon Pose Kapotasana, including Reclining Pigeon (Figure 4 Glute stretch)

- Cow-face Pose Gomukhasana

And from yoga for climbers, back to climbing for climbers.

I’m giving the final word to 80-year-old Gaby, who reminds us that climbing makes us feel“alive and strong and content”

So let’s keep climbing

🙏

DISCLAIMER: ALL ACTIVITIES DESCRIBED ON THIS WEBSITE ARE FOR GENERAL INFORMATION ONLY AND MAY NOT BE SUITABLE FOR EVERYONE. ALL EXERCISE CARRIES A SMALL RISK. ANYONE TRYING ANY OF THE ACTIVITIES DESCRIBED ON THIS WEBSITE ACCEPTS THIS RISK AND THE AUTHOR DISCLAIMS ANY LIABILITY FOR ANY ADVERSE EFFECTS CONNECTED WITH THESE ACTIVITIES.

Notes and References

- Sport England (2024) Active Lives Adult Survey NB It’s worth noting that this trend is improving quickly; according to a similar survey in 2008, far fewer older adults took the recommended amount of exercise. ↩︎

- Spirduso, W, Francis, K, & Macrae, P (2005) Physical Dimensions of Aging (2nd ed) Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics ↩︎

- Sipe, C (2025) Degrees of Functional Abilities, Demystified https://www.ideafit.com/degrees-of-functional-abilities-demystified/ ↩︎

- This article refers to normal ageing throughout, though it’s worth bearing in mind that our risk of disease, for example cancers, also increases with age. ↩︎

- https://www.climbing.com/culture-climbing/climbing-into-old-age-7-senior-climbers-share-their-experience-and-advice/ ↩︎

- Stebbins, R. A. (1982). Serious leisure: A conceptual statement. Pacific sociological review, 25(2), 251-272 ↩︎

- Self-determination theory is a framework for examining motivation which sees motivation as a spectrum from intrinsic, to extrinsic, to a complete lack of motivation. Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. ↩︎

- LeBlanc, M. (2018) Exploring the Motivations and Experiences of Middle and Older Aged Adult Rock Climbers University of New Brunswick ↩︎

Further Reading

- Article by German climber Imgard Braun https://climbing.plus/blog/irmgard-braun-6-tipps-fuers-klettern-50

- Article by Jesse Klein, drawing on tips from several of the USA’s top older climbers https://www.climbing.com/culture-climbing/climbing-into-old-age-7-senior-climbers-share-their-experience-and-advice/